Assessing Thirteen Years of Trout Stack-Ups in Galveston Bay

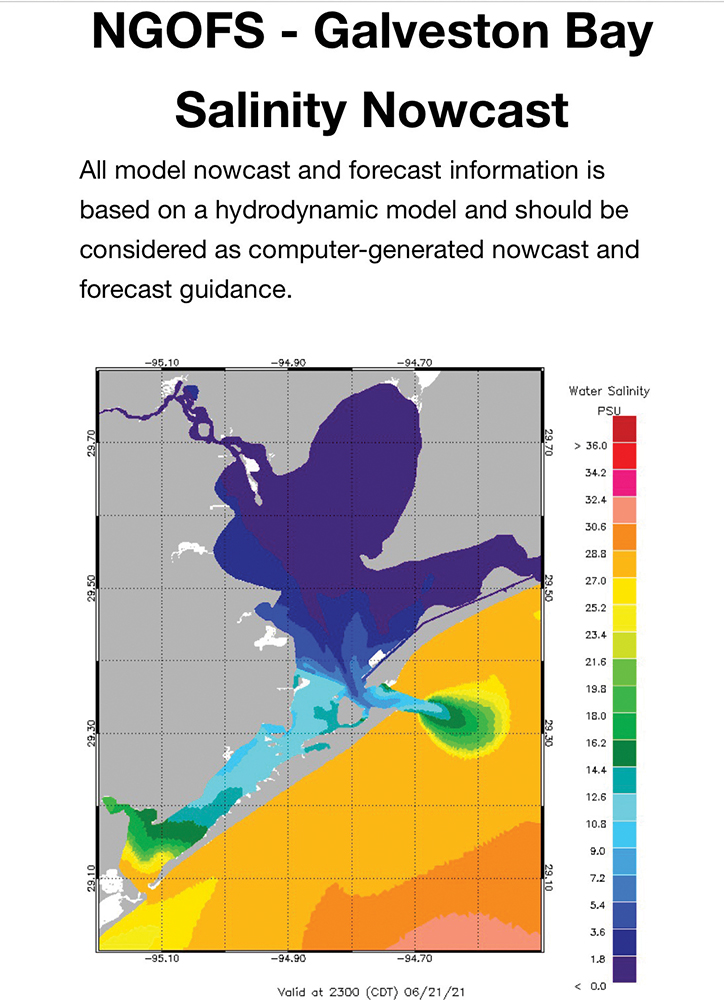

As I type, (June 21st) more than half of the Galveston Bay Complex has salinities ranging from 1 to 4 ppt (parts per thousand). It’s now been 7 years in a row that excessive amounts of local and upstream rainfall have resulted in unusually high inflows from the Trinity River and surrounding watersheds into our bay system. The same can be said for the San Jacinto River albeit to a lesser extent. Too much freshwater in the upper reaches of the system almost always results in trout stack-up situations in the lower portions of the bay. This has been the case once again.

Two of the most eccentric stack-ups I’ve ever witnessed occurred during the late-spring and early-summers of 2015 and 2016. Trout concentrated in the same two or three areas both years. The distinct difference was the size of the fish caught during the 2015 event. Many of them ranged between three- and seven-pounds. While the overall numbers of trout harvested during the 2016 stack-up period were similar, there was a noticeable size reduction with the majority of the fish falling in the two- to three-pound range.

The stack-ups of the past few years and what we’re currently experiencing pale in comparison to those of 2015 and 2016. When making these observations I think it’s important to understand the gradual changes in the dynamics leading up to each stack-up situation year after year. Nothing should be viewed in a vacuum, especially considering the many environmental and man-induced variables that help shape the ecology of a bay system.

Prior to September 13, 2008 Galveston Bay was home to about 24,000 acres of live oyster reef. Hurricane Ike made landfall in the wee hours of that dreadful morning bringing with it storm surges and sweeping currents that would ultimately cover 12,000 – 15,000 acres of live oysters in mud and silt. East Galveston Bay was the hardest hit losing approximately 80% of its oyster habitat. In 2009 the Texas Parks and Wildlife begun oyster reef restoration projects which were partially funded by federal grants. The majority of the initial planting of substrate took place in East Galveston Bay. River rock and limestone would eventually be planted closer to the ship channel and other areas. Many of the restoration sites were done in 15 to 30 acre increments and would ultimately result in hundreds of acres of new oyster reefs over the course of the next decade or so.

From 2009 through 2014 most of Texas experienced the worst drought since the mid-1950s with 2010 and 2011 being the worst. Many Texas reservoirs were at only 30% capacity. Bay salinity level at the mouth of the Trinity River reached as high as 34 ppt. To put this in perspective, salinities usually range from 30 to 36 ppt in the Gulf of Mexico. You may be wondering at this point why I jumped from reef restoration to droughts. Please just hang in there with me a bit longer as there are quite a few pieces to this puzzle.

During these drought years many of the new oyster growth areas that had been built by TPWD and other’s efforts fell prey to high-salinity thriving pathogens such as Perkinsus marinus (Dermocystidium). This disease causing pathogen has been responsible for massive mortalities of oyster reefs during extended drought periods. Similar to seagrasses in many South Texas bays, live oyster reefs are the base of the food chain for Upper Texas Coast bays. Not only do oysters feed on various types of microscopic plankton but they filter the water during the process, providing clearer water which allows more sunlight to penetrate through the water column. This in turn triggers more plankton growth. Under the right circumstances it’s a fascinating cycle that provides nutrients for everything up the chain beginning with lower-level consumers. In our bay system these lower-level feeders are made up of small crustaceans, shad, and many species of juvenile fish. In essence, live oyster reefs create a buffet for trout, reds, flounder and many other species of fish and marine life.

So what happens when those reefs die as many in fact did during the drought years? Where do trout find the next buffet? We have to determine which areas most of the shad, shrimp, mullet, etc. are going to gravitate toward. During drought situations these areas of attraction include lower-salinity areas such as back bays, river mouths and other upstream locales. These are exactly the locations where trout stacked up during the drought years. It didn’t take long for anglers to catch on to what was happening. 2009 through 2014 were the drought stack-up years that seldom get mentioned. Many trout were harvested during this period especially near the back reaches of Trinity and East Galveston Bays.

Enter the spring of 2015. Heavy rains, both locally and upstream, turned more than 60% of Galveston Bay into a big catfish pond within a matter of weeks. I was quickly on the move trying to find fishable waters for me and my clients. Monitoring of the Northern Gulf Operational Forecast System (Just Google NGOFS - Galveston Bay Salinity Nowcast) and the Lake Livingston Dam flow (http://lakedata.traweb.net) websites became a daily routine. We found trout concentrated in a few mid-bay deeper pockets of suitable salinity waters over what few live reefs were left. I was fortunate to find a couple of small patches off the beaten path because the main areas were a parking lot full of boats. The most popular stack-up area was a 60 acre oyster reef restoration site near the middle of East Galveston Bay. It wasn’t uncommon to see upwards of 75 boats there, even on weekdays.

These concentrations of trout got hit really hard by anglers. It was some of the easiest fishing I’ve ever witnessed. The same scenario took place in 2016 and it was Whack Fest Part 2 only this go-round the size dropped significantly as I mentioned earlier.

2017 appeared to be on track to be a so-called “normal” year. All the fresh water over the prior few years had helped purge the bay of oyster-killing parasites such as Dermo and oyster drills. The nutrients and salinity levels were finally conducive to healthy oyster growth and trout were settling in over their predictable spots.

Things were clicking right along until massive floods from Hurricane Harvey occurred in late-August of 2017, dropping bay-wide salinities to levels that were not tolerable for trout and many other species. The entire complex got purged of trout with the exception of a few small pockets in West and Lower Galveston Bays, but what was left in those areas wasn’t enough to wad a shotgun. In addition, too much fresh water killed most of the oyster reefs that were just making a comeback. Back to square one.

2018 through 2020 was yet another period where Trinity Bay remained mostly unfishable because of excessive river inflow. Lower Galveston, West Galveston and pockets of East Galveston bays got picked on pretty hard once again. There were stack-ups in many of the same areas as prior years but a 5-pound trout was newsworthy. With a few exceptions, most of the trout were just keepers with many undersized. The occasional “big” trout were caught in the surf, at the jetties and near passes. I tend to somewhat discount such fish because they are non-resident fish.

Now, here we are in 2021 and we’re faced with yet another stack-up scenario. But it’s not quite the same as in years past. 2021 started out as a somewhat normal year but we started experiencing a stack-up situation in early-May because Trinity Bay and the upper reaches of Galveston Bay once again became fresh. Currently, East Galveston Bay only has a few small pockets of fishable water because of fresh water flowing around Smith Point (from Trinity Bay), as well as Oyster Bayou and East Bay Bayou in the back of East Bay. This leaves Lower Galveston Bay and West Bay as the two main areas within the system holding suitable numbers of trout. The number of anglers hasn’t been reduced so there is more fishing pressure in smaller areas. The numbers of fish we’re catching are averaging just less than 2-pounds. There are many areas holding a ton of undersized trout as well. Four to six pounders are true outliers and 7- to 9-pound specks are unicorns. Most of the trout are in the 1- to 3-year age class, which I believe is largely attributable to the huge flush the bay received almost four years ago during the Hurricane Harvey floods.

These days, high currents and windy conditions cause the water to get muddy more easily compared to when we had vast areas of live reef. We’ve had days when we had to throw dark-colored soft plastics such as Morning Glory and Red Shad because the water had less than two inches visibility. We’ve also been inserting glass rattles into our soft plastics on some occasions. Currently, the bulk of the trout are near the bottom where salinity levels are higher.

There are some benefits of excessive fresh water flowing into our bays such as ushering in new nutrients and reducing oyster-killing parasites. One of the negatives include adverse effects on the growth and survival rates of trout eggs.

Our bays and estuaries hang in the balance between too much fresh water entering the bay and not enough. Hopefully, by the time this awesome magazine hits our mailboxes we will have seen reduced freshwater inflows. Once this occurs it shouldn’t take long with good tide exchanges and evaporation caused by the summer heat and wind to increase bay-wide salinities again. The sooner this happens the sooner everyone can spread out. It would bode well for the trout and their future. The longer we can keep speckled trout in our system the healthier our biomass will become and maybe we’ll start getting some legitimate size to them again one day.Galveston West Bay Jackfish