Memories of a Fisherman

He sat on the edge of the bed cradling his head in his hands, trying to shake the last remnants of sleep from his brain. He looked over to where his wife lay asleep, thankful the alarm hadn't wakened her.

He stood and stretched, joints creaking their discomfort as he flexed what remained of a once strong body. He looked again at his wife and smiled. There was a time she would have already been up, cooking his breakfast and making his lunch. Too many loads of laundry and raising his children had taken their toll.

He was heading for the kitchen when he paused at the door that lead to what they always called "his" room. He opened the door, flicked the switch, and stared at the contents of his special place.

The walls were adorned with memorabilia; paintings and aging fishing photos, charts of his favorite bays, and rod racks filled with the finest outfits money could buy. He stood a moment until his thoughts were interrupted by the sound of the morning paper banging the front porch screen. And then, as he had done so many times, he walked in and closed the door.

He gazed first at the chart of West Matagorda Bay, smiling as his finger traced the familiar route from Palacios down to Green's Bayou on Matagorda Peninsula. How many times had he run that course?

His finger drifted down the peninsula to Pass Cavallo. He chuckled to himself remembering the day he and a couple friends ran aground on a sand bar and the heck of a bad time they had getting the boat off. Odd, he thought, how something so scary at the time could seem comic now.

He moved down the wall and smiled at a yellowed photograph of him holding a large redfish in the surf. Sometimes he could barely remember being that young. And photos of people he cared about with fine catches, some of them gone, then finally to a chart of the Laguna Madre and Baffin Bay.

Baffin Bay. The land of plenty, they liked to call it. He remembered the first time he fished there and the great hope of someday landing a ten-pound trout from its ancient rocks. He had never been that lucky but he'd plugged his way through a slew of eights and nines. He always swore though, the one that somehow shook the trebles of a Broken-Backshe'd have gone ten or better!

He stared at a newspaper clipping his wife framed years ago about his fishing adventures and the writing he was doing for some outdoor magazines. Then he moved to the next wall, past the roll-top desk he hadn't opened in years, the wall with the rod racks.

He smiled and reached for a rod, then paused, as if to pay reverence. He lifted it lovingly, flexing it and marveling at its action and balance. Without realizing what his hands had done he was reeling the practice plug from the wastebasket in the corner. So many years of endless practice had honed the skill until it was automatic. Placing the rod back on the rack he took each of them in turn and repeated the motions.

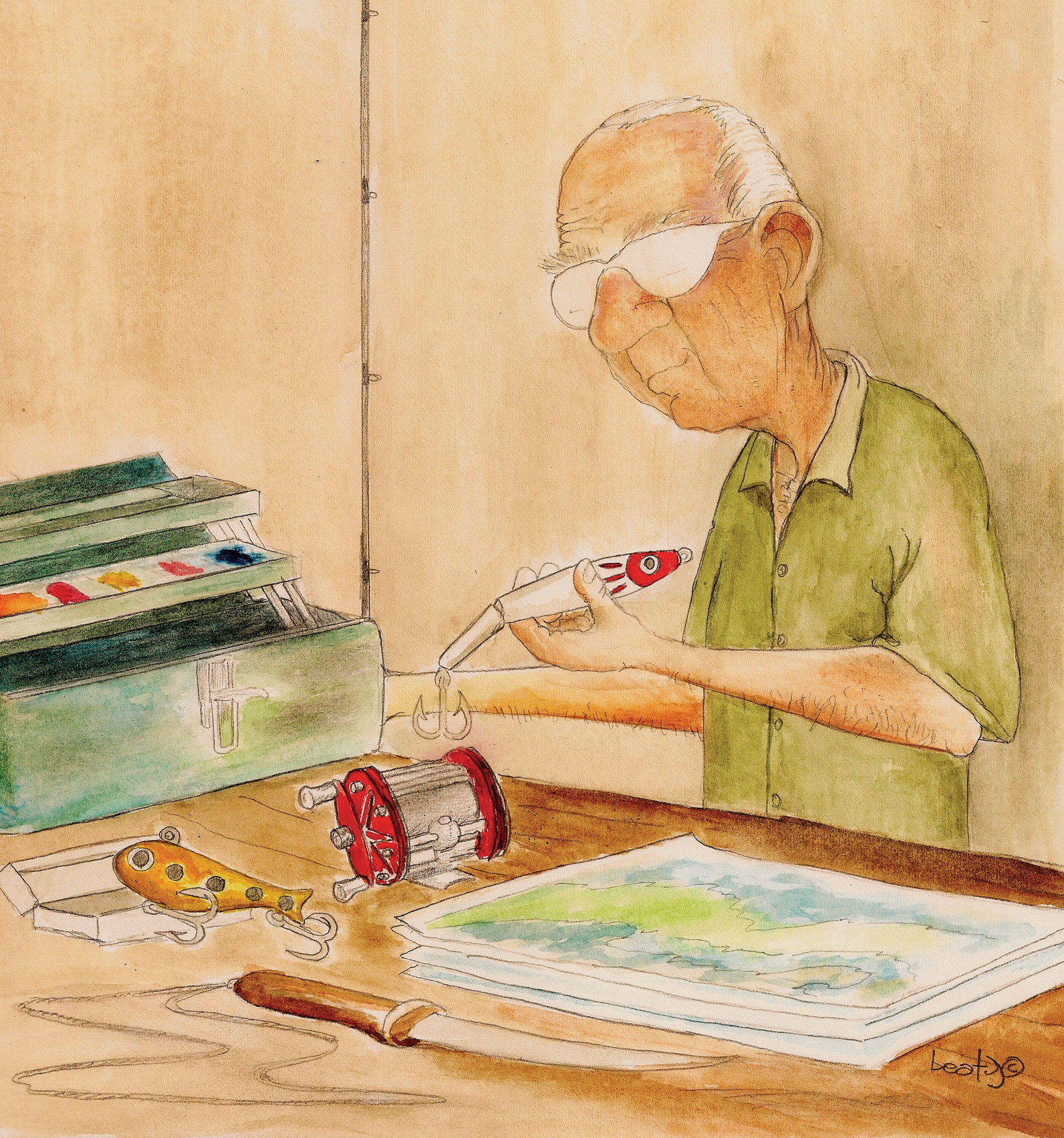

His eyes roamed to the open closet and felt a twinge of excitement as he spied the big tackle box, and then hurried to it as if it were a treasure chest newly discovered.

Placing it in the middle of the room he sat beside it like a child about to open a Christmas package. Snapping the latches and opening the lid his eyes drank in the contents; lures, reels, fillet knives, assorted paraphernalia, all neatly in trays.

The tooth-scarred Jointed Redfin. Oh how skeptical he'd been at first, and how ironic that it became one of his favorites, back in the day.

A smile came as he spied the M-Series Hump lure, still brand new. An elderly fisherman had presented it to replace the one he lost when the old gent's cast crossed his line. It had been a chance meeting, two strangers on a reef. What was that old man's name? He felt embarrassed that he couldn't remember.

He picked up his father's fillet knife, the one he wore around his neck on a cord through the sheath loop when he waded. "Keeps it out of the waterand handy when you need it," Dad always said.

He lowered the front panel of the big box and slid out a drawer that held a collection of Plugging Shortys. He ran his thumbnail across the deep tooth scars that were cut into several and wondered if he'd caught the trout that left them or maybe his dad.

He pondered the old days before limits and the first years after they'd been set; when a man could keep a decent day's catch with a clear conscience. As a boy he'd seen many a washtub of solid trout, helped fill a few, and the hundreds of limit stringers filled with trout and reds. Almost too heavy for a grown man. Those were the days all right.

He shook his head and frowned, "Where'd they all go?"

He remembered his fishing cronies and how they rarely got together anymore. They coaxed him half to death and finally he tried their new game, even bought clubs. But golf wasn't his thing.

Looking back, it was dishonest to say they never saw it coming. Oh there had been plenty of talk, but guys that knew their stuff hid behind the fact that they were still catching plenty. Most of them said that all the bays needed was a good flush, maybe a hurricane, "Mother Nature will fix it."

Then all of a sudden it was all over the news. Parks & Wildlife started saying their net samples were too low and the limits needed to be lowered. Well, he didn't really have a problem with that, and neither did most of his friends. But the new limits didn't solve the problem, and so they lowered them again. And then they lowered the boom.

The official notice said that the moratorium on saltwater fishing would last five years, after which new guidelines would be created. That was five years ago and he was anxious. The announcement was due today and he was anxious to see what the paper on the front porch had to say after five years of no-fishing.

He was desperate to know when he could once again wade the sand flats and shell reefs of his favorite bays but a nagging fear haunted him and he was afraid to pick up the paper. He knew his years were passing too quickly and he was afraid that five hadn't been enough to fix the problem that he and so many others just like him had helped create.

Back when they shut it down, they said that the pressure had simply become greater than the fishery could handle. But he knew better. In the back of his mind he knew all along that greed and ego were the real cause of the problem. And he also knew that it was guys like him; guys that should have known better.

He reached for the edge of the big desk to steady himself and slowly rose to his feet. It was time. Time to get the paper. Was he going fishing or spending the rest of the morning in his room–remembering?

He stood and stretched, joints creaking their discomfort as he flexed what remained of a once strong body. He looked again at his wife and smiled. There was a time she would have already been up, cooking his breakfast and making his lunch. Too many loads of laundry and raising his children had taken their toll.

He was heading for the kitchen when he paused at the door that lead to what they always called "his" room. He opened the door, flicked the switch, and stared at the contents of his special place.

The walls were adorned with memorabilia; paintings and aging fishing photos, charts of his favorite bays, and rod racks filled with the finest outfits money could buy. He stood a moment until his thoughts were interrupted by the sound of the morning paper banging the front porch screen. And then, as he had done so many times, he walked in and closed the door.

He gazed first at the chart of West Matagorda Bay, smiling as his finger traced the familiar route from Palacios down to Green's Bayou on Matagorda Peninsula. How many times had he run that course?

His finger drifted down the peninsula to Pass Cavallo. He chuckled to himself remembering the day he and a couple friends ran aground on a sand bar and the heck of a bad time they had getting the boat off. Odd, he thought, how something so scary at the time could seem comic now.

He moved down the wall and smiled at a yellowed photograph of him holding a large redfish in the surf. Sometimes he could barely remember being that young. And photos of people he cared about with fine catches, some of them gone, then finally to a chart of the Laguna Madre and Baffin Bay.

Baffin Bay. The land of plenty, they liked to call it. He remembered the first time he fished there and the great hope of someday landing a ten-pound trout from its ancient rocks. He had never been that lucky but he'd plugged his way through a slew of eights and nines. He always swore though, the one that somehow shook the trebles of a Broken-Backshe'd have gone ten or better!

He stared at a newspaper clipping his wife framed years ago about his fishing adventures and the writing he was doing for some outdoor magazines. Then he moved to the next wall, past the roll-top desk he hadn't opened in years, the wall with the rod racks.

He smiled and reached for a rod, then paused, as if to pay reverence. He lifted it lovingly, flexing it and marveling at its action and balance. Without realizing what his hands had done he was reeling the practice plug from the wastebasket in the corner. So many years of endless practice had honed the skill until it was automatic. Placing the rod back on the rack he took each of them in turn and repeated the motions.

His eyes roamed to the open closet and felt a twinge of excitement as he spied the big tackle box, and then hurried to it as if it were a treasure chest newly discovered.

Placing it in the middle of the room he sat beside it like a child about to open a Christmas package. Snapping the latches and opening the lid his eyes drank in the contents; lures, reels, fillet knives, assorted paraphernalia, all neatly in trays.

The tooth-scarred Jointed Redfin. Oh how skeptical he'd been at first, and how ironic that it became one of his favorites, back in the day.

A smile came as he spied the M-Series Hump lure, still brand new. An elderly fisherman had presented it to replace the one he lost when the old gent's cast crossed his line. It had been a chance meeting, two strangers on a reef. What was that old man's name? He felt embarrassed that he couldn't remember.

He picked up his father's fillet knife, the one he wore around his neck on a cord through the sheath loop when he waded. "Keeps it out of the waterand handy when you need it," Dad always said.

He lowered the front panel of the big box and slid out a drawer that held a collection of Plugging Shortys. He ran his thumbnail across the deep tooth scars that were cut into several and wondered if he'd caught the trout that left them or maybe his dad.

He pondered the old days before limits and the first years after they'd been set; when a man could keep a decent day's catch with a clear conscience. As a boy he'd seen many a washtub of solid trout, helped fill a few, and the hundreds of limit stringers filled with trout and reds. Almost too heavy for a grown man. Those were the days all right.

He shook his head and frowned, "Where'd they all go?"

He remembered his fishing cronies and how they rarely got together anymore. They coaxed him half to death and finally he tried their new game, even bought clubs. But golf wasn't his thing.

Looking back, it was dishonest to say they never saw it coming. Oh there had been plenty of talk, but guys that knew their stuff hid behind the fact that they were still catching plenty. Most of them said that all the bays needed was a good flush, maybe a hurricane, "Mother Nature will fix it."

Then all of a sudden it was all over the news. Parks & Wildlife started saying their net samples were too low and the limits needed to be lowered. Well, he didn't really have a problem with that, and neither did most of his friends. But the new limits didn't solve the problem, and so they lowered them again. And then they lowered the boom.

The official notice said that the moratorium on saltwater fishing would last five years, after which new guidelines would be created. That was five years ago and he was anxious. The announcement was due today and he was anxious to see what the paper on the front porch had to say after five years of no-fishing.

He was desperate to know when he could once again wade the sand flats and shell reefs of his favorite bays but a nagging fear haunted him and he was afraid to pick up the paper. He knew his years were passing too quickly and he was afraid that five hadn't been enough to fix the problem that he and so many others just like him had helped create.

Back when they shut it down, they said that the pressure had simply become greater than the fishery could handle. But he knew better. In the back of his mind he knew all along that greed and ego were the real cause of the problem. And he also knew that it was guys like him; guys that should have known better.

He reached for the edge of the big desk to steady himself and slowly rose to his feet. It was time. Time to get the paper. Was he going fishing or spending the rest of the morning in his room–remembering?