Little Fish, Big Future: Texas Observes an Upsurge in Juvenile Red Snapper

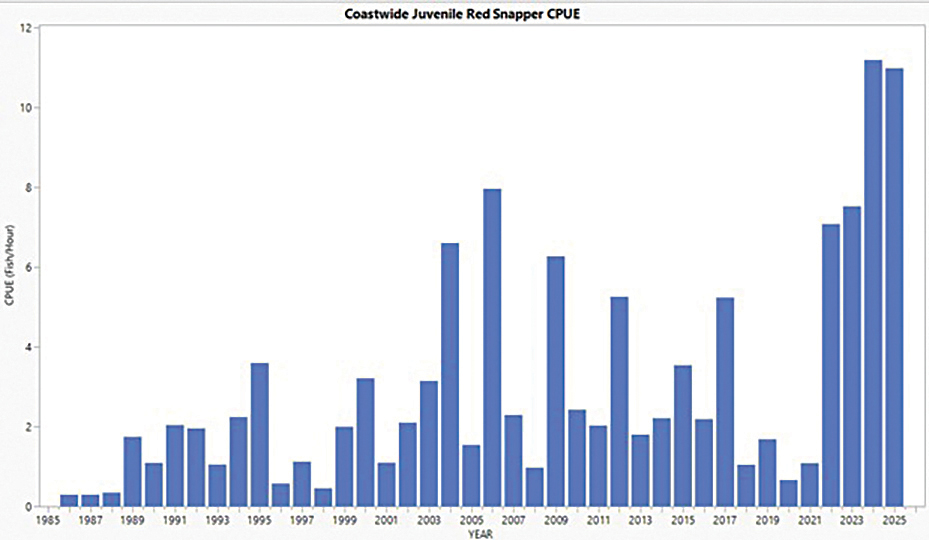

Figure 1: Coastwide juvenile red snapper CPUE (fish/hour) from 1986-2025.

*Data from 2020 incomplete due to COVID-19

*Data from 2025 still being processed

Long prized for their culinary appeal, economic value, and vital ecological role in the Gulf ecosystem, red snapper (Lutjanus campechanus) are a commercially significant and highly popular game fish found in the western Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of America. Juvenile red snapper closely resemble adults, sharing the same rosy-red coloring that fades to white at the belly, along with red eyes and an angular snout. However, juveniles are typically paler in color and display a distinctive dark spot on their sides below the soft rays of the dorsal fin—a feature that fades with maturity. Juvenile red snapper inhabit shallow waters with sandy or muddy bottoms in low-relief habitats such as shell rubble or scattered debris, typically at depths under 30 meters. As important components of the Gulf’s food web, juvenile red snapper are active carnivores, feeding on zooplankton, small fish, and worms, while also serving as a vital food source for larger fish and marine mammals.

Texas Parks and Wildlife Department (TPWD) Coastal Fisheries staff conduct monthly surveys to monitor marine resources in Texas’ Gulf waters. Each month, sixteen one-square-mile grids—randomly selected from areas within 15 miles of major jetties along the Texas coast—are sampled during daylight hours. Crews use an 18.7-foot-wide trawl pulled for ten minutes along a depth gradient to collect samples. Once on deck, the catch is quickly identified, measured, counted, and released back into its habitat. These samples often contain an impressive diversity of species, ranging from juvenile finfish and shrimp to squid and even bryozoans. Routine TPWD Gulf sampling began in 1986 and has continued steadily—aside from a brief pause during the COVID-19 pandemic—providing invaluable long-term data on coastal conditions in Texas waters.

Harvest of red snapper in the Gulf dates back to at least the 1840s. By the 1970s, however, both fishermen and scientists began voicing concerns as red snapper numbers noticeably declined. In response, the National Marine Fisheries Service (now NOAA Fisheries) introduced management regulations in the mid-1980s, including minimum size and bag limits, in an effort to reduce fishing pressure and rebuild the population. When NOAA conducted its first official stock assessment in 1988, those concerns were confirmed: the red snapper fishery showed clear signs of being overfished, with ongoing overfishing occurring.

By around 1990, the red snapper population had reached a critical low point. The spawning potential ratio (SPR)—a metric comparing the reproductive output of a fished population to that of an unfished one—had fallen to just 2%. In other words, the stock was producing only 2% of the eggs expected from an unfished population. It was evident that more aggressive management actions were necessary to preserve both the species and the fishery. NOAA responded by implementing annual catch quotas to cap recreational and commercial harvests and further tightening bag limits. In the early 1990s, TPWD surveys began showing a modest increase in the number of juvenile red snapper encountered in coastal trawl samples.

A few years later, the Sustainable Fisheries Act of 1996 marked a major turning point in rebuilding the red snapper population. Regulatory measures—including reduced bag limits, increased size limits, license and gear restrictions, refined seasons, and annual quotas—were enacted to promote recovery. Beginning in 1997, in-season monitoring strategies such as fishery-dependent surveys and enhanced enforcement allowed agencies to better manage recreational season lengths and prevent quota overages. To address one of the largest sources of juvenile red snapper mortality—bycatch—NOAA-certified Bycatch Reduction Devices (BRDs) became mandatory for all commercial shrimp trawls in 1998.

BRDs are gear modifications designed to allow non-target species, such as red snapper, to escape while retaining the intended catch, thereby reducing bycatch and supporting sustainable fishing practices.

In 2000, the red snapper fishery transitioned to a fixed recreational season, with season dates based on pre-season projections of when quotas would be reached. That same year, bag limits were reduced again, and minimum size limits were increased. TPWD surveys continued to reflect a gradual rise in juvenile red snapper abundance through the early 2000s. Despite these efforts, the 2005 stock assessment showed limited improvement, with spawning biomass reaching only 4.7%. This prompted development of a more rigorous rebuilding plan. Under this strategy, recreational and commercial quotas and bag limits were further reduced, an Individual Fishing Quota (IFQ) program was implemented for the commercial fishery, and additional bycatch-reduction measures were enacted.

NOAA stock assessments released in 2009, 2013, and 2015 all documented a steady rebound in red snapper abundance. The 2015 assessment indicated that spawning biomass had tripled since 2005. These findings led to increases in annual quotas for both recreational and commercial fisheries between 2010 and 2019. During this same period, however, TPWD observed a slight decline in juvenile red snapper counts in their surveys. Reef Fish Amendment 50, passed in 2020, shifted some management authority for private recreational fishing in federal waters to Gulf Coast states. Under this framework, each state receives a portion of the private-angling red snapper quota and may independently set season lengths, bag limits, and minimum size limits. Since the transition to state management, Texas anglers have benefited from longer seasons, with the most recent 2025 season lasting 173 days. In addition, TPWD Coastal Fisheries staff have documented a notable increase in juvenile red snapper appearing in Gulf trawl samples in recent years—a trend that has generated both optimism and further scientific inquiry.

While these observations are encouraging, continued monitoring and effective management of the red snapper population remain critical. According to the most recent stock assessment in 2018, the current SPR is estimated at 20%, below the target SPR of 26%. Advances in fishing and boating technology, along with increased accessibility, are likely to drive higher catch rates in the future. Even with increased annual quotas, recent red snapper seasons have often closed early due to quotas being reached quickly. Maintaining a balanced age structure within the population is another essential factor, as egg production increases with fish size and age. Allowing today’s juvenile red snapper the opportunity to mature will be key to ensuring long-term sustainability. Work is currently underway on the next red snapper stock assessment, expected to be completed within the next year. Its results will help guide future management decisions and support a healthy red snapper population—for today’s anglers and those yet to come.