More Shucks for Your Bucks: A Cost-Benefit Analysis of Oyster Restoration Strategies

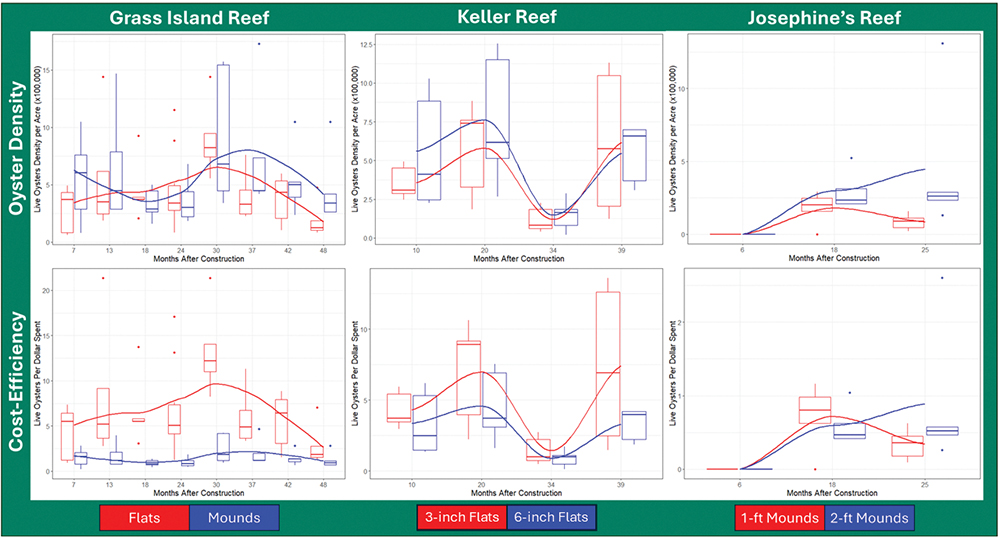

Figure 1: Monitoring data from experimental reefs at Grass Island (left), Keller (center), and Josephine’s (right). Oyster density, reported as live oysters observed per acre, is shown on the top three graphs. Cost efficiency, reported as live oysters produced per dollar spent, is shown on the bottom three graphs. Experimental treatments are differentiated in red or blue, as described below each column.

Oyster reef restoration has become an increasingly prevalent strategy to manage and conserve oyster populations in Texas. To date, the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department (TPWD) has restored over 1800 acres of reef across our coastline. TPWD typically conducts oyster restoration by placing bare “cultch” (shell or rock material) on degraded reef, thereby providing supplemental substrate for larval oysters to settle on. However, in recent years, the cost of cultch material and placement has risen exponentially—totaling only $56 per cubic yard in 2009 and peaking at $271 per cubic yard in 2023. This increase in cost has presented a challenge to restoration practitioners, prompting TPWD to explore new strategies to make the most of limited funds.

To evaluate which restoration approaches were most effective at producing and sustaining adult oysters with the greatest cost-efficiency, TPWD designed and constructed multiple experimental restoration reefs in Aransas, Keller, and Espiritu Santo Bays. The experimental designs tested the differences resulting from (1) deploying cultch as thin, continuous layers versus consolidated mounds, (2) deploying variable depths of cultch layers, and (3) constructing reefs with variable vertical relief. Each reef was monitored twice per year following construction using hydraulic oyster patent tongs—essentially a giant shellfish claw machine—to evaluate restoration success over time. The monitoring data were extrapolated and standardized to report total adult oyster production per acre of restored bay bottom and then analyzed with respect to the total costs related to each restoration strategy.

Grass Island Reef, in Aransas Bay, was restored using a combination of different cultch placement configurations. Parts of the reef were restored in a “flats” configuration, using a three-inch layer of rock spread evenly across the bottom. Other sections were restored in a “mounds” configuration, which utilized consolidated piles of rock that were ten feet in diameter, two feet tall, and spaced twenty feet apart. Within three years after construction, TPWD observed consistently higher oyster densities on the cultch placed as mounds. However, the mound approach requires approximately five times the volume of cultch to cover the same spatial footprint of the flats and is therefore much more expensive. As a result, the flats approach was actually more cost-efficient at generating adult oysters over the duration of this study.

Keller Reef, in Keller Bay, was restored entirely using the flats configuration. At this site, we tested rock evenly spread across the bay bottom in either three-inch or six-inch layers. TPWD monitoring data indicate that these experimental treatments produced comparable oyster densities to each other. Similar to our results at Grass Island, our analysis concluded that the strategy of using less cultch to cover the same footprint resulted in higher oyster production per dollar spent—as a six-inch layer costs twice as much as a three-inch layer.

At Josephine’s Reef in Espiritu Santo Bay, all cultch was placed in the mounds configuration. Mounds were constructed to extend either one or two feet off the bay bottom, allowing us to compare the effects of differing vertical reliefs. Over the duration of our monitoring, we observed a gradual increase in oyster density on the two-foot mound treatment. After two years, however, we detected a decline in oyster density on the one-foot mounds. This difference in oyster production was large enough that, to date, the taller mounds are more cost-efficient despite being twice as expensive to build. Anecdotal evidence, recorded in TPWD biologists’ field notes, suggests that this trend may be driven by restored reef sinking into the mud at this site.

Collectively, monitoring data from these three experimental restorations provide insight that can help inform TPWD’s future oyster restoration efforts. All treatments tested were successful at increasing oyster density compared to pre-restoration conditions, and within two years were producing oysters at rates comparable to or exceeding those observed on nearby natural reefs. These studies provide evidence that Texas bays are generally not “spat limited.” That is to say that if practitioners place supplemental cultch material in a suitable area, they can typically expect larval oysters to settle on it. Our results suggest that increasing the availability of exposed hard substrate by deploying ‘thinner’ layers of cultch can maximize the cost-efficiency of oyster production, at least in the short-term. This conclusion supports the philosophy of the “maintenance restoration” approach, in which one-to-two inches of cultch material are spread over moderately degraded reefs.

While TPWD’s experimental restorations highlight the benefits of using less cultch to bolster oyster production while minimizing costs, we acknowledge that there is still value to implementing strategies that are not immediately as cost-efficient. Our trends, particularly at Josephine’s Reef, demonstrate that the approaches tested may exhibit different degrees of resilience to natural and anthropogenic processes and placing higher densities of cultch may ultimately be more cost-efficient in the long-term. Moreover, oyster production is just one metric of restoration success. For example, although mounds were shown to produce fewer oysters per dollar spent, they likely perform better at dissipating wave energy and protecting vulnerable shorelines from erosion. Denser placements of cultch may also be more resilient to periodic disturbances like major storms and heavy dredging activity.

TPWD plans to continue monitoring our experimental restorations to better evaluate long-term success. These on-going assessments provide critical feedback that can assist the Department in adaptively managing Texas’s oysters for both the ecosystem services they provide and the benefit of those that rely on the resource for their livelihood.