Mysterious Microscopic Skaters

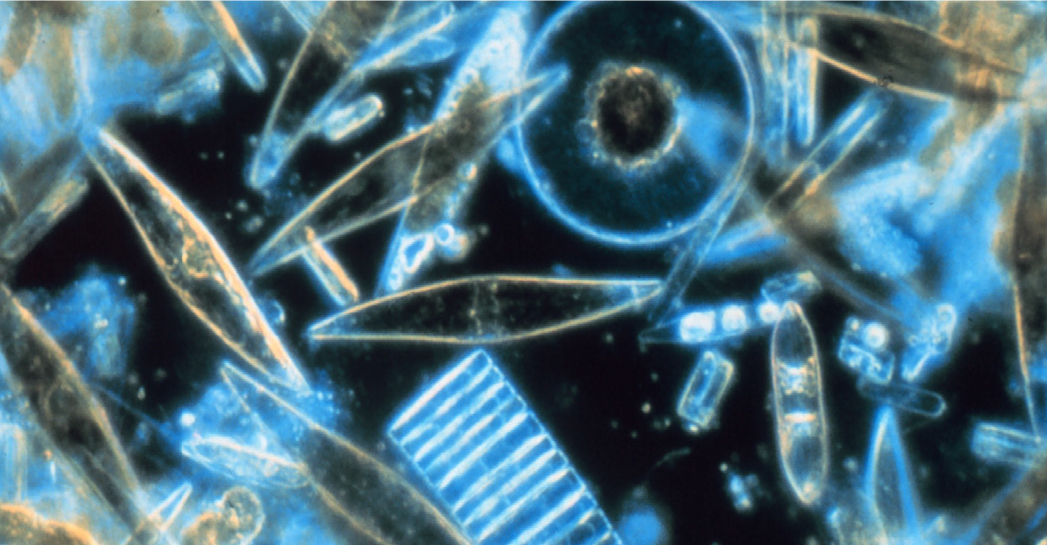

Under freezing conditions in the Arctic, diatoms are very active and

skate along the ice. Credit: Dr. Gordon T. Taylor, NSF Polar Programs

For years, few scientists have devoted much time to studying Arctic

diatoms, single-celled algae enclosed within a wall of glass-like silica.

These bizarre organisms, after all, appeared frozen in the sea ice, stuck in

dormancy, or so many scientists believed. In reality, however, ice diatoms

are quite active—skating along the ice at temperatures as low as 5ºF

(-15ºC). That’s what scientists recently discovered when they collected

diatoms from the Arctic during an expedition in the Chukchi Sea, the

body of water that sits between Alaska and Siberia above the Bering

Strait, and brought them back to their lab to study them.

Back at their lab, the researchers introduced the specimens to ice that resembled the diatoms’ natural environment. Then they watched as the diatoms sped along tiny channels in the ice. The algal cells glided along without the use of any appendages and without the kind of movement, such as wiggling, that other limbless organisms might use. The diatoms do it by secreting mucus that sticks to the icy surface at one end, creating a sort of anchored rope that they can pull themselves along. What stunned the researchers, though, was that the ice diatoms could move in this way at such cold temperatures. No other diatoms or other single-celled plants or animals had been documented as moving at temperatures this low.

Now the researchers are working to understand how diatoms function at such cold temperatures and, even more importantly, how they fit into the broader ecosystem of the Arctic. With the long-term existence of Arctic ice threatened by a warming global climate, researchers want to know: What will happen when the diatoms’ icy highways are gone?

Back at their lab, the researchers introduced the specimens to ice that resembled the diatoms’ natural environment. Then they watched as the diatoms sped along tiny channels in the ice. The algal cells glided along without the use of any appendages and without the kind of movement, such as wiggling, that other limbless organisms might use. The diatoms do it by secreting mucus that sticks to the icy surface at one end, creating a sort of anchored rope that they can pull themselves along. What stunned the researchers, though, was that the ice diatoms could move in this way at such cold temperatures. No other diatoms or other single-celled plants or animals had been documented as moving at temperatures this low.

Now the researchers are working to understand how diatoms function at such cold temperatures and, even more importantly, how they fit into the broader ecosystem of the Arctic. With the long-term existence of Arctic ice threatened by a warming global climate, researchers want to know: What will happen when the diatoms’ icy highways are gone?