Breaking Down the North Badlands

Found at the intersection of Baffin Bay and the Upper Laguna Madre, two of our state’s most respected big trout fisheries, the Badlands sits perfectly positioned to produce specks of epic proportions. Some parts of the area hold water of decent clarity when wind speeds crank up off the Gulf, and also when they whistle behind the passage of strong cold fronts. The Badlands has variable depths and a bottom covered by four different constituents—sand, mud, grass, and rocks; these facts enhance its potential for consistent productivity.

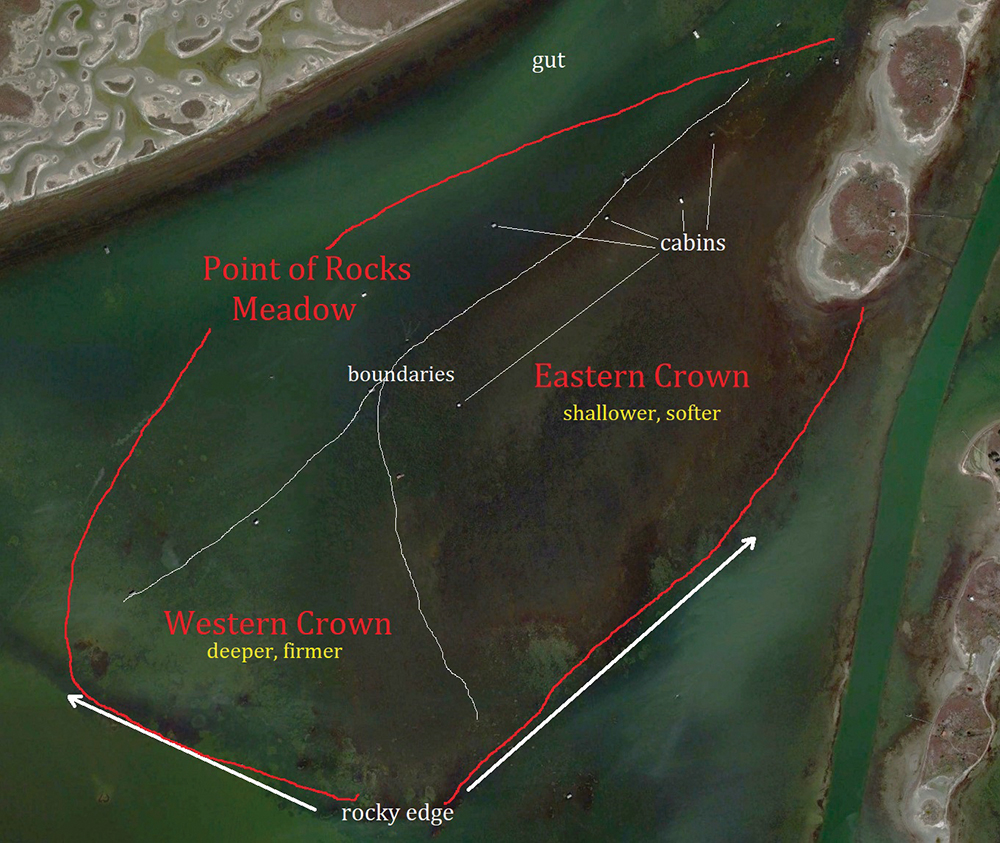

Some parts of the Badlands produce better numbers of big trout than others. I and most of my friends have encountered more monster trout in the North Badlands than in other parts of the area. This section of the Badlands has two dominant features—a relatively deep, grassy flat extending south from the gut wrapping around the Point of Rocks, and farther south, a shallower, soft flat covered with thick grass beds and scattered rocks. A long line of floating cabins approximately marks the boundary between these two parts, which I call the Point of Rocks Meadow and the Badlands Crown.

Much of the time, the water in the Point of Rocks Meadow proves too deep for wading. Less often, low tides allow anglers to wade the entire area. Grass covers most of the bottom on this flat, which stretches for over a mile at its widest point; a few small serpulid rocks and numerous sets of potholes create anomalies which provide targets for lure chunkers when the water runs clear. On the northeast margin of the meadow, a deep gut funnels water from north to south, out of the intracoastal and into the shallows surrounding the cabins. Identifying specific sweet spots in the Meadow proves difficult, since grass beds grow and die off, and because tide level plays such a prominent role in determining which parts of the flat the fish temporarily prefer.

South of the long chain of cabins, on the Badlands Crown, identifying micro-spots with high potential proves somewhat easier for folks with trained eyes. The grassy bottom in the eastern two-thirds of the Crown, normally covered by water less than thirty inches deep—often less than twenty—feels much like banana pudding. Wading anglers who choose to try and cover lots of ground in this place often become exhausted and frustrated, some more likely to find themselves stuck in the mud than landing a memorable trout. The deeper western part of the Crown has a firmer bottom, with less complete grass coverage. Easier wading in this area, combined with its long, well-known track record of producing giants, makes it one of the most popular places frequented by guides and gurus looking to scratch the big-trout itch.

Both of these spacious areas produce trout reaching the extremes of what’s possible in the Lone Star State, as many famous anglers have documented. I caught my longest trout to date here, and I could name several other well-known anglers who’d say the same. I’m aware of a loaded list of trout measuring well over thirty inches—up to and exceeding thirty-two—as well as plenty of heavy beasts stretching the Boga to the ten-pound mark and beyond, up to about twelve, which were caught in these famous places. Most, but certainly not all, of the biggest specimens bit during cold-weather events, from about Thanksgiving through Spring Break.

The North Badlands produces trophies best during cold snaps, though big trout certainly populate parts of it year-round. The most important variables affecting exactly which parts of this area will provide the best potential in a given moment include tide level, wind speed and direction, and water temperature. At a basic level, lower tides enhance fishing in deeper parts of the area, while higher tides enhance the shallower parts. Colder water temperatures accentuate the potential of the shallower parts of the area, while warmer ones favor the deeper parts. These generalizations do have merit, but only when considered in a more complete context, given other aspects of a particular situation.

The two most important environmental variables are water temperature and tide level, with water temperature more important in the cold part of the year, and tide level reigning supreme during the warmer months. Conventional wisdom suggests trout in the Badlands will retreat into deeper water when extreme frontal events cause water temperatures to plummet during the first half of winter. Hypothetically, trout in the North Badlands use the deep channel lying close to the Point of Rocks to make their way into the intracoastal and its relatively warmer water. As soon as conditions moderate, they return to the Point of Rocks Meadow. Anecdotal evidence, in the form of excellent catches of big trout under conditions like these, supports the theory.

As conditions moderate slightly more, many of the biggest trout in the area will show up in the shallows atop the Badlands Crown. Water temperatures ranging from about 50 to 54 degrees best enhance the potential for catching wall-hangers in this area from December through February. Once water temperatures warm into the mid-50s, the reliability of this pattern falls apart. Other factors further complicate the situation. Bitter north and northwest winds whistling in the wake of strong cold fronts will turn the shallow water covering the Crown ugly brown. The deeper water covering the flat lying closer to the Point of Rocks holds its clarity longer in such situations.

Normally, in winter, the best scenarios for catching huge trout on the Crown take place in water of marginal clarity. An angler’s knowledge of the locations of sweet spots on the flat becomes critical when silt in the water hides the bottom from probing eyes. Another productive winter pattern plays out in these locations when strong onshore winds (southeast) push most of the water off the Crown and muck up what’s left. Then, good numbers of big trout often move into the deeper, cleaner water of the Point of Rocks Meadow, where anglers wielding topwaters and slow-sinking twitch baits can trick them—sometimes catching impressive numbers of five- to seven-pound fish, with an occasional bigger one thrown in to ice the proverbial cake.

In warmer months, the same strong southeast winds will muck up most of the water in the Badlands as a whole, creating a juicy scenario in the eastern part of the Crown—especially when those winds veer more to the east. During events like these, the water covering the grassy bottom close to the spoil island separating the Eastern Crown from the intracoastal maintains decent clarity, and savvy anglers willing to brave the walk can encounter some epic fish to reward their efforts. This scenario also works well when winds swing to the north of due east, during any timeframe, but especially during the moderate months of spring and fall.

A skilled angler chunking lures could catch a magnum trout in the North Badlands during any month on the calendar. I caught the longest trout of my career here in May; a customer also caught one of the longest trout taken on my charters in this area during the last full month of spring. During the warm months, the two most important environmental factors enhancing the potential for catching big trout in the North Badlands become wind speed and tide level. The best scenarios generally include conditions in which quiet onshore winds blow softly across the Crown, with a tide level in the medium-to-high range. In conditions like those, the water on the wide, shallow flat will run green to clear, as long as brown tide is either absent or only minimally present.

In such situations, anglers tossing floating plugs like One Knockers and slow-sinkers like Paul Brown Fat Boys can pull monsters out of hiding by focusing their efforts around rocks and potholes. Sometimes big trout will rest against grassy seams created by pothole edges; other times, they’ll sit atop the rocks themselves, waiting to ambush prey. Particularly in spring, they tend to like perching on the rocks and don’t show much willingness to move off their edges to strike. These situations can necessitate presenting topwaters or floating twitch baits directly over the boulders.

In the shallow, generally clear waters of the eastern portions of the Crown, Floating Fat Boys or Paul Brown Original Lures work well. Without rattles, these lures create less disturbance than conventional topwaters; their stealth sometimes makes them more effective in attempts to trick old trout into striking in the shallows. Additionally, the ease of presenting floaters at appropriate speeds in water less than twenty inches deep enhances their potential in places like these. As is the case anywhere, catching finicky fish on the Crown sometimes requires throwing soft plastics; dangling them under small corks helps anglers work them at the proper pace through the shallows.

In the warmest months, anglers can expect to catch a few big trout in the Point of Rocks Meadow, especially when steady onshore winds muck up the Crown and blow the tide out. In better conditions, with good water clarity and slightly higher tide levels, the western half of the Crown offers ripe opportunity, though the number of big trout present in the shallowest parts of the area likely runs lower than in cold water. Obviously, targeting small numbers of fish scattered far and wide across vast flats requires patience, diligence, and an acceptance of a lower success rate.

Nevertheless, this area does attract plenty of anglers during the hot months, for good reasons. Winds often whisper at the start of a typical summer day, then pick up significantly around lunchtime. Anglers wading central and western portions of the Crown and throwing topwaters regularly reap rich rewards while the sun is low. Later, when wind speeds ramp up, standing upwind of rocks and throwing soft plastics as close as possible to their wind-blown fronts works better. These scenarios represent just a few of the many plans known to make anglers’ dreams come true in the rightly famous place known as the North Badlands.